Meeting the Queen often left people feeling disoriented. Although many had seen her countless times in photos and portraits, encountering her in person could be overwhelming, like seeing a beloved family portrait come to life.

When Michelle Obama first met the Queen at Buckingham Palace in 2009, she struggled to focus, writing later, “Sitting with the Queen, I had to force myself to stay present and not be overwhelmed by the grandeur and the reality of meeting an icon.”

A friend of mine, a magazine editor, once attended one of the Queen’s “informal” lunches. A senior courtier suggested he use the restroom beforehand, just in case—advising that some previous guests had “had an accident” when meeting the Queen. The comic novelist Kingsley Amis, who was invited to a similar lunch in 1975, was so anxious about a potential mishap that he adhered to a strict diet and even took Imodium before his visit, worried he might have an embarrassing incident in front of Her Majesty.

Another distinguished guest, who was known for his sophisticated demeanor and had met many famous figures, found himself rendered speechless by the Queen’s presence. He described feeling physically ill, his mind going blank, and resorted to complimenting a non-existent brooch. He was astonished by his own reaction.

Sometimes, people saw the Queen as a familiar figure from their personal lives. As a child, I was convinced that our nanny was secretly the Queen, imagining she moonlighted at the Palace.

Rock star Phil Collins once met the Queen and, perhaps overwhelmed, began whistling the theme from Close Encounters of the Third Kind. When the Queen asked about it, Collins was struck dumb, leading to an awkward explanation from radio presenter Terry Wogan.

The Queen’s ability to radiate calm and presence often led to guests speaking without thinking. In 1969, US Ambassador Walter Annenberg’s response to the Queen’s inquiry about his residence became infamous for its convoluted phrasing, immortalized by a BBC recording.

The Queen’s ability to inspire even seasoned figures to blurt out nonsense was evident. Actress Miriam Margolyes, when asked by the Queen what she did, declared herself the “best reader of stories in the whole world,” despite her usual role being much more modest.

When the Beatles met the Queen in 1965, their teenage infatuations seemed to cloud their conversation. John Lennon’s mind went blank, and Paul McCartney’s attempt at humor fell flat, leaving the Queen nonplussed. Despite the awkwardness, Lennon later reflected warmly on her kindness.

Even dignitaries like David Blunkett, whose guide dog barked at Vladimir Putin during a state visit, experienced the Queen’s gentle and perceptive responses. She reassured Blunkett with a comforting gesture toward his dog, understanding his discomfort.

The Queen’s corgis were not only her companions but seemed to reflect her own nature—free from the constraints imposed on her by royal life. When David Nott, a surgeon recently returned from a traumatic stint in Syria, struggled to respond to the Queen’s inquiry, she turned to her dogs, offering a moment of solace and normalcy through their presence.

These moments with the Queen reveal not just the disarming effect of her presence but also the warmth and humanity she extended to those who found themselves in her company.

News

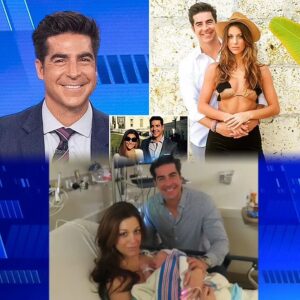

“Jesse Watters and Wife Emma DiGiovine Shock Fans with Surprise Baby News—Meet Their New Baby Girl and the Heartwarming Story Behind the Announcement!”

Fox’s Jesse Watters and wife Emma DiGiovine glow as they welcome new baby girl to the world FOX News host Jesse Watters and his wife Emma DiGiovine…

Linda Robson broke down in tears, saying she would DIE TOGETHER with her best friend Pauline Quirke on live television, leaving everyone stunned. What happened?

Linda Robson has spoken publicly about the heartbreaking dementia diagnosis of her long-time friend and Birds of a Feather co-star, Pauline Quirke. Last month, Pauline’s husband, Steve…

Pete Wicks Admits He ‘Cried Several Times’ Filming Emotional New Rescue Dog Series – The HEARTWARMING Moments That Left Him in TEARS!

‘They have transformed my life for the better’ Star of Strictly Pete Wicks admitted he “cried several times” while filming his new documentary, Pete Wicks: For Dogs’ Sake. A lover…

Gino D’Acampo just stirred up social networks with his FIRST POST after being fired from ITV

Celebrity chef and TV star Gino D’Acampo has been accused of sexual misconduct as over 40 people have come forward amid his alleged wrongdoing A defiant Gino D’Acampo has…

This Morning presenter prepares to become homeless, family home worth £4m about to disappear

The This Morning presenter lives in Richmond with his wife and children This Morning star Ben Shephard lives less than 30 minutes away from the ITV studios, in a beautiful home…

Stacey Solomon in tears and forced to walk off camera as Sort Your Life Out fans say ‘LIFE IS CRUEL’

Stacey Solomon had to step away from the camera, overwhelmed with emotion, while filming her show ‘Sort Your Life Out’ as she assisted a family from Leeds in decluttering their…

End of content

No more pages to load